Blogger’s Note: Rick Legault of Ottawa, Canada and I share an appreciation for the multi-faceted symbolism in medieval cathedrals and especially Chartres Cathedral in France, a place we have both visited at different times. ![]()

![]() Since we first met online a couple years ago, we’ve traded emails about our questions, speculations, insights, and resources. Our correspondence has enriched me. Rick opened my eyes to the meaning of astronomical elements in Chartres Cathedral, helping me appreciate it and other cathedrals all the more. For all of that, I am grateful. I’m pleased to share his guest post about the iconography of the zodiac at Chartres with you. It’s a draft of an article that will appear in final form at http://independent.academia.edu/RichardJLegault.

Since we first met online a couple years ago, we’ve traded emails about our questions, speculations, insights, and resources. Our correspondence has enriched me. Rick opened my eyes to the meaning of astronomical elements in Chartres Cathedral, helping me appreciate it and other cathedrals all the more. For all of that, I am grateful. I’m pleased to share his guest post about the iconography of the zodiac at Chartres with you. It’s a draft of an article that will appear in final form at http://independent.academia.edu/RichardJLegault.

____________________________________________________________________________________________

Mandorling – I thank you Mike for accepting this article as a guest post on your blog. I owe you and yours a debt of gratitude not only for your inspiring work but for taking some superb photos for my series of draft papers on Chartres Cathedral. I can never really get to the bottom of sacred images. There is always another connection to pursue, another layer of meaning, another analogy, another allusion. In homage to your Mandorlas in our Midst blog, I’ve taken to using the word mandorling to designate the pursuit of these meaningful connections.

So now, I invite you and your readers to come along with me to a time: AD 1145, to a place: Chartres, to meet the Chartrians and do a bit of mandorling about some of the images they used depict the annual activities of their medieval way of life and, more importantly, their knowledge of time-tracking and astronomy.

The Zodiac and Labors of the Months – In Gothic art, the calendar cycle of annual activities is depicted so often in stone, glass and illuminated manuscripts that it is possible to define a fairly standardized iconography of images known as the Labors of the Months. Two examples are shown below in Figure 1 and Figure 2. To each month is assigned a typical rural activity such as pruning in April, hunting and falconry in May, planting and weeding in June, harvesting in July, threshing in August, pressing grapes in October, butchering livestock in November and, inevitably, feasting in December.

Figure 1 – Nobleman Feasting in December, Zodiac Window, Chartres Cathedral, France

These activities and the iconography can vary a bit from place to place with different activities taking place earlier or later in the year depending on local climate, length of seasons and customs. The Labors of the Months images are always fairly easy to understand especially when the artists label each month with their names in letters, as in Figure 2.

Figure 2 – Labors of the Month and Zodiac Signs, Zodiac Window, Chartres Cathedral, France

Very frequently the Labors of the Months are accompanied by the even more standardized iconography of the twelve signs of the Zodiac, a medieval adaptation of the traditional astronomical lore of late Greek and Roman antiquity. Astronomy has always been essential to keep calendars on track with the natural cycles of time – the days, the months, the seasons and the years. In Gothic art the Labors of the Months and the Signs of the Zodiac are almost always arranged in the standard chronological order of the calendar, as shown in Figures 3 and 4. A major exception to this standard chronological order is displayed in the archivolt sculptures of the Royal Portal of Chartres Cathedral, shown and mapped in Figures 1a, 1b and 1c.

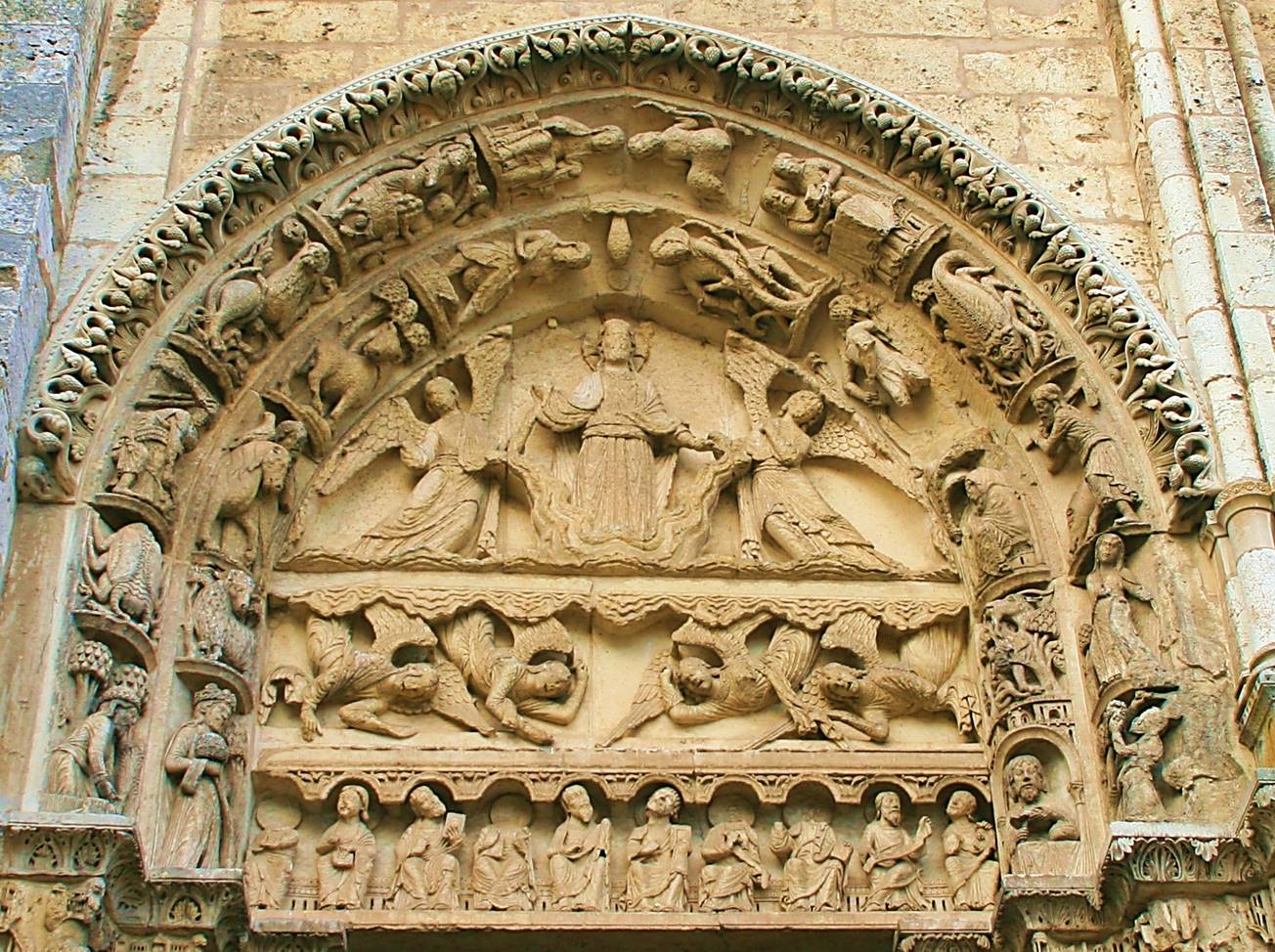

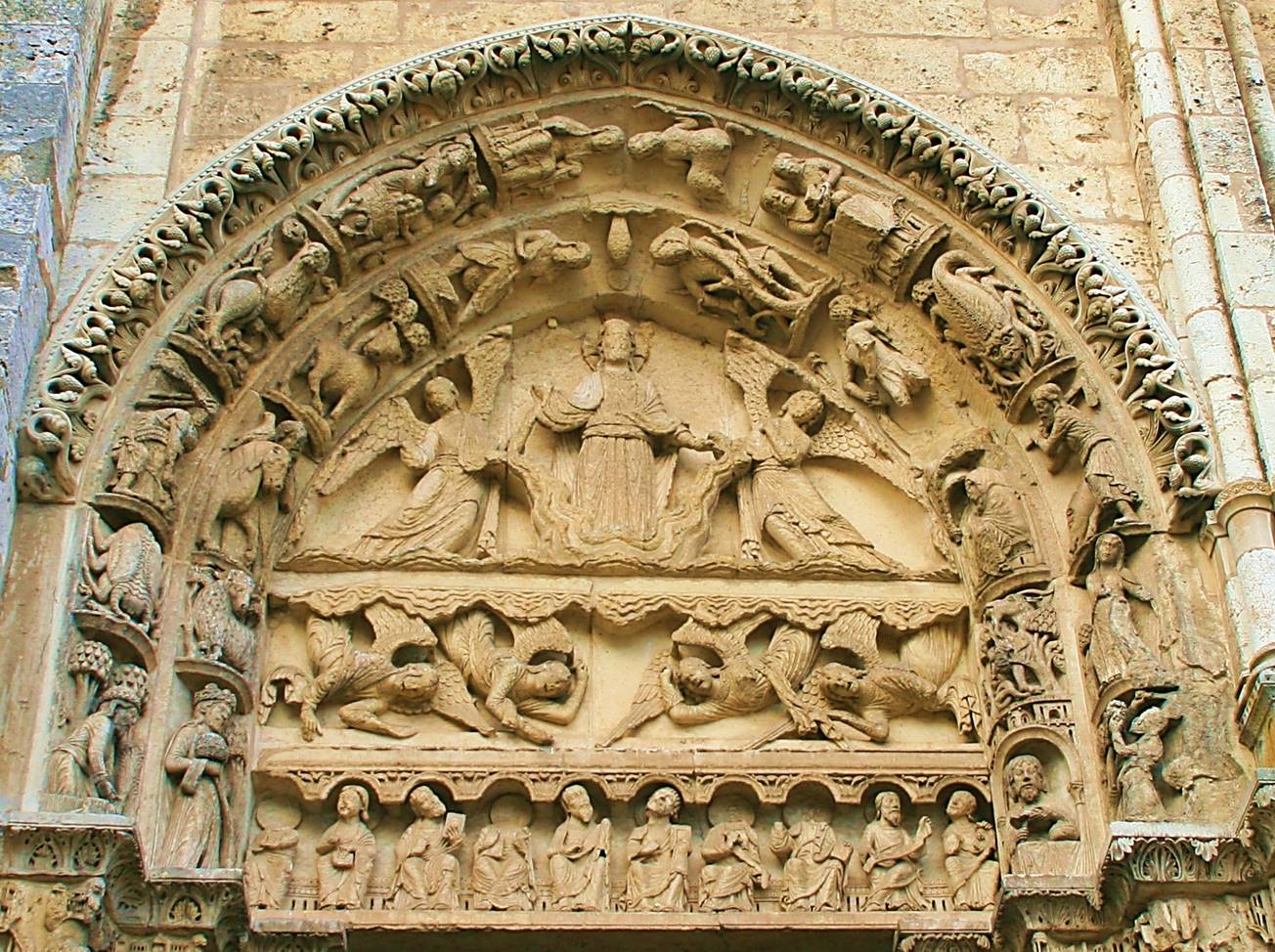

Figure 1a – The chronological disarray of Ten Zodiac Signs and Twelve Labors of the Months surrounds a Contemplation of Creation scene over the leftmost door of the Royal Portal (c. 1145).

Zodiacs at Chartres – There are several Calendar and Zodiac images at Chartres Cathedral. The most prominent and well known are in the archivolts above two of the three doors of the Royal Portal. Here, the Signs of the Zodiac and Labors of the Months are in disarray, in nothing even close to their proper chronological order. They are also disconnected because only 10 zodiac signs are grouped with the 12 labors of the months over the leftmost door, while two signs – Gemini and Pisces – are split off from that group, and placed separately over the rightmost door. There, the central imagery of the Incarnation is surrounded by angels using censors to sanctify the medieval curriculum of the Seven Liberal arts represented by seven sages of antiquity and female personifications. The separate placement of Gemini and Pisces within this group seems oddly out of place – a curiosity arousing anomaly that taxes the observer for an explanation and makes the topic ideal for a mandorling.

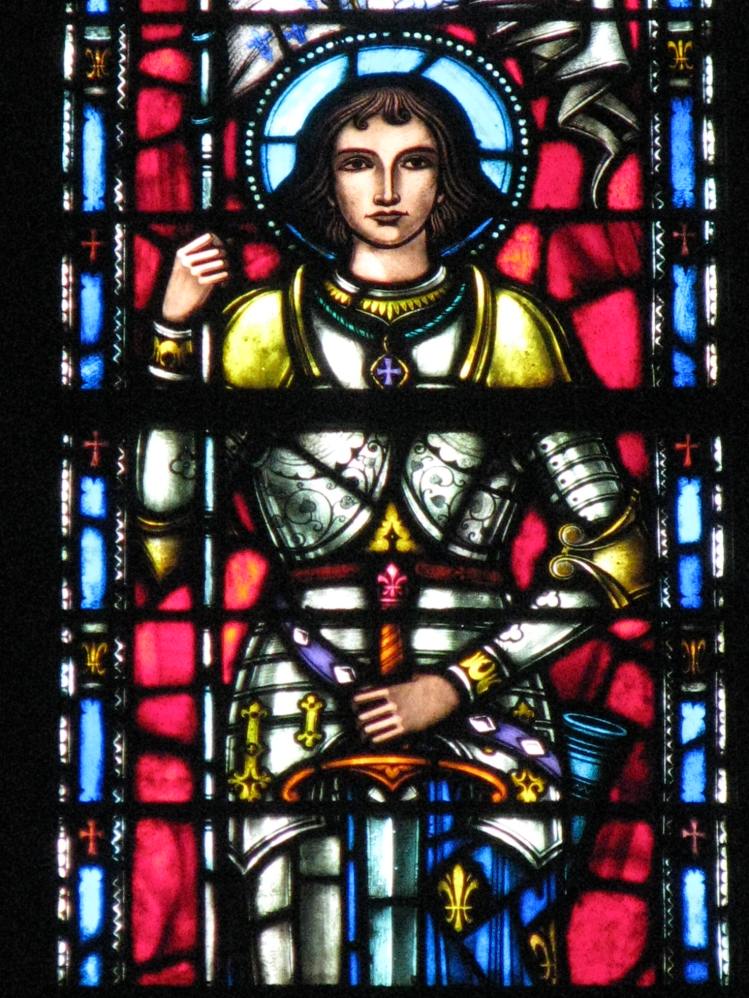

Figure 1b – Gemini and Pisces (highlighted) and the Seven Liberal Arts are sanctified by Angels with censors surrounding images of the Incarnation over the right door of the Royal Portal (c. 1145).

This disarray and disconnectedness is not the case with other calendar and zodiac images in the Cathedral. For example a second Zodiac in a stained glass window in the ambulatory, shown in Figure 2, ends with December and Capricorn at the top, after working its way up through the months and the zodiac in their proper chronological order with one exception. The exception is the transposition of April and May and of Taurus and Gemini – a transposition I can understand as neither an error on the part of the original glaziers nor a botched restoration. As we go along, you will see why I think this transposition is a later and secondary re-affirmation of the reason for the disconnection of the stone Zodiac in the Royal Portal.

A third and much later Zodiac Cycle in the outermost archivolt of the rightmost door of the North Transept Porch, shown in Figure 3, is in perfect calendrical sequence, as is the one in the much later Astronomical Clock, shown in Figure 4. An easily overlooked and less well known fifth Zodiac Cycle, shown in part in Figure 5, is delicately tooled into a slender colonette behind the statues in a jamb of the Royal Portal. As I have not seen it in its entirety I don’t know if it is in proper sequence with the calendar.

Figure 3 – Chartres North Porch Zodiac – The signs and the monthly labors in the archivolts of the North Porch follow the calendar. The cycle starts with January at the left bottom, continues through June at the top and ends in December, at the right bottom. The two extra figures at each end depict the seasons Winter and Summer: men in seasonally appropriate attire (c. 1215 – restored). The cut and paste close-ups, in random order, are from a modern French postcard.

Figure 4 – The Face of the Zodiacal Clock at Chartres shows the signs in their proper calendrical sequence, with the Sun on the cusp between Leo and Virgo and the Moon about ¾ full, c. 1525-28.

Figure 5 – Cancer, Sagittarius, Libra and Gemini finely tooled on a colonette in a jamb of the Royal Portal, c. 1145.

I think there can be no question that ignorance or error is the cause of the odd disorder and disconnectedness of the Zodiac of the Royal Portal. The correct chronological order of the signs of the Zodiac was too well-known in medieval culture of the 12th Century. Their cosmology, astronomy and time reckoning methods, inherited from classical Greek and Roman teachings, were read in the Latin works of medieval natural philosophers such as Beothius, the Venerable Bede, Isidore of Seville, Abbo of Fleury and numerous others. The exceptional interest in and knowledge of astronomy among the Chartrians, from the days of Bishop Fulbert of Chartres (c. 1006) up to the chancellorship of Thierry of Chartres (c. 1145) is a well-documented fact of history. Accordingly, I am persuaded that the disarray and disconnectedness of this Royal Portal Zodiac was a matter of deliberate design. The designers, alas, left no written record of the reasoning behind their choices, no record of the teaching they intended to convey with this very peculiar design. We do not even know for sure who they were. We have only the sculptures to speak, as it were, for themselves.

Nevertheless, we do have considerable and reasonably reliable knowledge of the cultural context of medieval Christian theology, natural philosophy, cosmology and astronomy that the Chartrians read about, wrote about and taught in the mid-twelfth century at their Cathedral school. If we accept the idea that their cathedral is a stone and glass record of these teachings, then I think the best way to understand the meaning of the Disconnected Zodiac, is to look for clues in the Chartrian readings, writings and teachings of which the stone and glass version, is but a duplicate. Extracting the meaning of the Disconnected Zodiac in this way is the goal of this paper.

Medieval Astronomy – The understanding of the Chartrians of the structure of the cosmos and of astronomy, at the time they built the Royal Portal (c. 1145), followed the teachings of Plato and Claudius Ptolemy. Up to that time they had had only an incomplete Latin translation of Plato’s Timaeus and for Ptolemy, only second and third hand summaries, compilations and commentaries from other authors of late antiquity. Ptolemy’s actual books, however, were just beginning to become available, arriving from Latin translators of Arabic versions during this period of the twelfth century: the Tetrabiblos c. 1138 from Plato de Tivoli, the Planisphere c.1143 from Hermann of Carinthia, and the Almagest c. 1175 from Gerard of Cremona.

Medieval Zodiac – The stately procession of the fixed stars, including the constellations of the Zodiac, across the night sky was well known to medieval philosophers and astronomers. The name Zodiac comes from the Greek zōdiakos kuklos (ζoδιακoς κύκλος), meaning “circle of animals”. Perhaps the longest lasting game of connect the dots of all time, the constellations and Zodiac, to this day are still a convenient identification, mapping and memory tool. Following Plato and Ptolemy, these constellations were considered to reside on an outer-most sphere of fixed stars that never moved with respect to each other. The entire sphere with its stellar panorama revolved in an east-west direction around the Earth daily.

Inside this outermost sphere – and in front of the zodiac constellations to an observer on earth – they could also see the heavenly pageantry of a second procession. This was the wanderings of seven stars Plato and Ptolemy had called planets because they were not fixed and could be seen to move along from night to night, month to month, and even year to year, from west to east (prograde), against the background of the twelve constellations of the Zodiac. Their seven planets, each on their own sphere nested one inside the other, were the Moon, Sun, Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter and Saturn. This Ptolemaic Model, as we now call it, was frequently illustrated in manuscripts using a series of concentric circles as seen in Figure 6. While some of the planets were seen to sometimes reverse direction and move backwards (retrograde) through the Zodiac for short periods of time, in general, their movement was seen as an ongoing west-east procession, with each planet completing its zodiacal cycle in its own unique period of time.

Figure 6 – Ptolemaic Planetary Model in Medieval Manuscripts

![]() The Disconnected Zodiac – The sculptures of the Royal Portal include the twelve signs of the zodiac, arranged in a strangely disordered manner. Ten appear in disarray over the left door, none over the middle door and two, Gemini and Pisces, over the right door. Many of the authors who describe this arrangement comment on the strange disorder without offering any satisfactory explanation. In 1964 Adolf Katzenellenbogen said the splitting off of the two signs “poses a particular problem for which no definite solution may be offered.” In 2008 Philip Ball said “We no longer know how to read this code.” In 2009 John James attempted a mystical New-Age astrological explanation the meaning of which, frankly, impedes a reasoned understanding. An exception is Margot Fassler who in 2010 said that Pisces and Gemini over the Incarnation doorway are symbolic of the annual feast days of the Annunciation on 25 March in Pisces and of John the Baptist on 24 June in Gemini. Her idea is indeed a meaningful calendrical and contextual fit with the Incarnation images. However, it does not help me understand why the Chartrians would have singled out and given greater prominence to the Annunciation and the Baptist rather than other liturgical dates of equal or arguably greater significance: Advent between 27 November and 3 December in Sagittarius, the Nativity itself on December 25 in Capricorn, Epiphany on 6 January also in Capricorn, the Presentation of Jesus at the Temple (Candlemas) on 2 February in Aquarius, or the Transfiguration of Jesus on 6 August in Leo. Fassler’s idea also gives no reason as to why the other 10 signs are displayed in such messy disarray.

The Disconnected Zodiac – The sculptures of the Royal Portal include the twelve signs of the zodiac, arranged in a strangely disordered manner. Ten appear in disarray over the left door, none over the middle door and two, Gemini and Pisces, over the right door. Many of the authors who describe this arrangement comment on the strange disorder without offering any satisfactory explanation. In 1964 Adolf Katzenellenbogen said the splitting off of the two signs “poses a particular problem for which no definite solution may be offered.” In 2008 Philip Ball said “We no longer know how to read this code.” In 2009 John James attempted a mystical New-Age astrological explanation the meaning of which, frankly, impedes a reasoned understanding. An exception is Margot Fassler who in 2010 said that Pisces and Gemini over the Incarnation doorway are symbolic of the annual feast days of the Annunciation on 25 March in Pisces and of John the Baptist on 24 June in Gemini. Her idea is indeed a meaningful calendrical and contextual fit with the Incarnation images. However, it does not help me understand why the Chartrians would have singled out and given greater prominence to the Annunciation and the Baptist rather than other liturgical dates of equal or arguably greater significance: Advent between 27 November and 3 December in Sagittarius, the Nativity itself on December 25 in Capricorn, Epiphany on 6 January also in Capricorn, the Presentation of Jesus at the Temple (Candlemas) on 2 February in Aquarius, or the Transfiguration of Jesus on 6 August in Leo. Fassler’s idea also gives no reason as to why the other 10 signs are displayed in such messy disarray.

I think we need to look elsewhere to find a better way to understand the disconnected zodiac. The two disconnected signs are placed among a double set of images that represent the wisdom in the teaching syllabus of the Trivium and Quadrivium of late pagan antiquity. Accordingly, rather than look to the liturgical calendar, I think it makes better sense to look for meaning in readings and texts of Theology and Natural Philosophy, subjects for which the Masters of the School of Chartres were then, and are to this day, most well known. I propose working with the idea that the disarray and disconnectedness of the sculptures intentionally fit with the overall theme of the entire portal as a depiction of the theological concept of time using the three key moments of time in Christian theology: Creation, Incarnation and Second Coming. In the context of the Quadrivium, the teachings of the four liberal arts that deal with numbers, order, quantity and measurement, it makes sense that the depiction of the zodiacal signs would have something to do with using astronomy to measure and quantify time. The additional depiction over the center door of astrolabes, shown in Figure 7, is consistent with this idea because astrolabes are instruments of astronomical measurement and computation associated primarily with orderly observation, timekeeping and way finding.

Figure 7 – Angels unwrapping astrolabes in the archivolts of the Royal Portal, center door c. 1145.

Hypothesis – I think the extraction of Pisces and Gemini for placement separately over the right door may depict a Chartrian representation of the amount of time elapsed from the moment of Creation to the moment of the Incarnation, in other words, the duration of the Old Testament period. The idea is that the Chartrians may have used the concept of astronomical precession and what we now call Zodiacal Ages to depict the estimated elapsed time as spanning from early in the Age of Gemini to the beginning of the Age of Pisces.

Year of Creation – The question of how old Creation was had preoccupied Christians from the earliest times. For instance, Mario Livio writes that, as early as the year 169, Theophilus of Antioch had concluded “that the world had been created some 5,698 years earlier),” in other words in 5529 BC. Many estimates of this kind were widely known in medieval times from Christian writers and traditions that had used biblical chronologies to calculate a variety of estimates of the time of Creation. Over a dozen of these estimates are listed in Figure 8. The average of this dozen puts the count between Creation and Incarnation at 5,449 years with a standard deviation of about 114 years or 2 percent of the average. This is a pretty good match with the traditional Anno Mundi (Year of the World) count of 5,500 years. Texts of many of these authors and of others who cited them were available for reading in Chartres at the time of Thierry of Chartres’ Chancellorship, as listed in Figure 9.

Figure 8

Figure 9

Astronomy and Precession – From the known contents of Thierry of Chartres’ book Heptateuchon, listed in Figure 10, there is additional good evidence that knowledge of the astronomy of Ptolemy, Hyginus, and Al-Kwarizmi was at hand among the Chartrians. This knowledge included the concept of astronomical precession, understood then as the very slow movement of the position of the equinoxes backwards (retrograde) through the constellations of the zodiac.

Figure 10

What is now called general precession in modern astronomy is the observation that the equinoxes – two points where the celestial equator intersects the ecliptic – slowly move backwards relative to the background stars. An equinox occurs when the Sun is on one of these two intersection points. Their movement takes place at a rate very close to 50.29 arc seconds per year or one full degree of arc in just over 71.5 years or one full 30-degree sign of the zodiac in about 2,145 years. Professor Roy Bishop provides an excellent and up to date description of precession in The Royal Astronomical Society of Canada’s Observer’s Handbook 2017: “As a result of the combined precession of the equator and precession of the ecliptic, the equinoxes (the intersection points of the celestial equator and the ecliptic) drift westward (retrograde) about 50.29ʺ per year (a period of approximately 25,800 years. […] The Vernal equinox was located in the constellation Gemini 7,500 years ago [c. 5483 BC], in Taurus 4500 years ago, and in Aries 3000 year ago. It moved into Pisces from the “first point of Aries” around the beginning of the Christian era 2000 years ago, at roughly the same time as Hipparchus discovered the precession of the equinoxes.”

Moreover, the entry in a NASA glossary for a Great Year or Platonic Year states, “the period of one complete cycle of the equinoxes around the ecliptic [i.e. 360 degrees around the zodiac] is about 25,800 years.”

Generally, precession is measurable by observation of long-term displacement of the Sun’s position in the Zodiac on the day of the equinoxes. Considering precession involves a displacement the of the Sun’s position, and the Sun was then thought of as a planet, precession may, following Plato’s definition, be taken as a legitimate marker to measure the passage of time. Today, a Zodiacal Age is the name used for the amount of time the vernal equinox spends in a given segment of the zodiac spanning 30 degrees of the ecliptic or about one twelfth of a Platonic Year (360/30 = 12). The duration of time you assign to a Zodiacal Age or to a Platonic Year depends directly on the rate of presession you use to calculate it. The inaccurate and excessively slow rate first found by Hipparchus and used by Ptolemy was challenged in the Middle ages.

The concept of astronomical precession was nothing new to Medieval Christianity. In the third century, Origen, who was read at Chartres, considered it so well-known that he used it to argue that astrological divination and prognostication was fakery and a heresy: “There is a well-known theorem which proves that the Zodiac, like the planets, moves from west to east at the rate of one part in a hundred years, and that this movement in the lapse of so long a time changes the local relation of the signs […]. We are thus taught that the most learned in these matters cannot show beforehand what the Lord intends to bring upon every nation (Origen The Philocalia XXIII, 18).”

In antiquity, Claudius Ptolemy, following Hipparchus, had put the rate of precession substantially slower than the modern value, at about 1 degree per 100 years, or one full 30-degree sign of the zodiac in 3,000 years. This was the rate known to Origen. Later in later medieval times, the Arab astronomer Al-Battani (c.855 – 929) found much of Ptolemy failed to agree with observations and had measured the rate of precession as being much faster, a value close to 54.5 arc seconds per year, which is one degree in about 66.1 years, or one full 30-degree sign of the zodiac every 1,982 years. This is much closer to the modern value of about 2,145 years. Al-Battani wrote about this in his book Kitab al-Zij. This book appeared in the Latin West in 1116, translated as De motu stellarum (On the Motion of the Stars) by Plato of Tivoli who is reported to have worked in Barcelona from 1116 to 1138 (O’Connor 1999 and Minio-Paluello, 2008).

Al-Battani at Chartres – There is solid textual evidence that Thierry of Chartres, Chancellor at Chartres during the construction of the Royal Portal, was familiar with the more advanced astronomy of Al-Battani. The evidence is written in Hermann of Carinthia’s Preface to his translation from the Arabic of The Planisphere of Claudius Ptolemy. In this Preface, Hermann dedicates his work to his former teacher – Thierry of Chartres – whom he describes as the greatest living master of the liberal arts and of natural philosophy in these words: “To whom, therefore, can I dedicate that which is the deepest principle and root of all studies of humanity rather than to you, who, I know, and therefore plainly confess, hold the first position in philosophy in these times, and are, as it were, an-unmoveably secure anchor in the turbulent storms of ever-changing doctrines? If it pleases the Gods, may envy not make me, like the indolent masses, voluntarily allow myself to lie, or hide the truth before you, most worthy teacher Thierry, in whom, I am convinced, the soul of Plato has once again been brought down from heaven and fitted to mortal man (Translation Burnett 1978, my emphasis).”

The fact that Hermann and Thierry shared knowledge of Al-Battani’s work in astronomy is also evident in the Preface. It contains a passage naming Arabic authors and texts of astronomical science, indicating these were well-known to of both of them: “From these, and `in the Greek tongue, he collected two volumes: the Sintasis for the first discipline, and the Tettastis for the second – in Arabic called the Almagest and the Alarba. Al-Battani has appropriately made the Almagest more concise (?), and Abü Marshar has, no less appropriately, expanded on the Alarba (Translation Burnett 1978).”

Al-Battani’s work, from its first arrival in Europe to this day, has been most well-known for its challenges to Ptolemy’s observational accuracy and especially for improving Ptolemy on the rate of precession. No modern biographer fails to mention it.

Dating Creation Using Precession – Anyone using Al-Battani’s rate of precession, Biblical traditions dating the time of creation at an average of 5449 BC and working backwards from the birth of Christ pegged at year AD 1, the dawn of the Age of Pisces, would place the time of creation early in the Age of Gemini. Accordingly, the interval of time between Creation and the Incarnation may have been depicted over the right door of the Royal Portal using the two signs Gemini and Pisces as symbolically corresponding to a Biblically estimated interval of time between the Age of Gemini and the Age of Pisces, as shown in Figure 11.

Figure 11

This explanation of the reason for disconnecting Gemini and Pisces from the rest of the zodiacal signs over the left door and placing them separately over the right door is, of course, a hypothesis. It follows on the facts of cultural context that the Chartrian community and Royal Portal designers, had access to the absolute most recent Latin translations of Arabic and Greek works of astronomy. As Peter Ellard says, “They were on the cutting edge of the natural sciences of their day, and this included the use of astrology [and astronomy] texts from Islamic sources which were only very recently made available (Ellard 2007).” Moreover, this hypothesis is also consistent with the Royal Portal depictions of the most recent astronomical technology, the astrolabe, which also had just recently arrived from the Andalusian Arabs.

An Ugly Fact? – Whether working in cultural history or in science, any damn fool can propose a hypothesis or theory to explain a puzzling phenomenon. It is the philosopher Sir Karl Popper who most often gets credit for formalizing, in the 1930s, the idea of falsifying hypotheses as the essential element of the scientific method. According to Popper no hypothesis can ever be proven, but one can be falsified, meaning that it can and should be scrutinized by decisive experiments, observations and tests. My favorite and I think the most eloquent phrasing of this idea is in Thomas Huxley’s presidential address to the British Association for the Advancement of Science for 1870. He hit the nail of the falsifiability principle squarely on the head, and much earlier than Popper, when he described the idea as, “the great tragedy of science – the slaying of a beautiful hypothesis by an ugly fact.”

How well does my hypothesis stand up to the rigors of falsifiability and testing? Well, to be intellectually honest and with great humility I must admit that there are strong opinions out there about the scarcity of primary sources from the late classical and medieval periods that show unequivocally that anybody ever used precession or Zodiacal Ages as a timekeeping method to delineate historical periods or to measure and quantify epochs of time. The ugly fact dangling like a guillotine blade above the neck of my hypothesis is that serious literature on the matter opposes my hypothesis. For instance, Nicholas Campion, a respected cultural historian and specialist in the history of astronomy and astrology, writes: “There is though, not a single extant example of the use of precession of the equinoxes to predict the future by astrologers until the late nineteenth century. There are indeed arguments that precession was used by astrologers in the ancient world, but they are based entirely on the retrospective interpretation of circumstantial evidence and lack any textual support. […] Literary evidence is not everything but, when it is entirely absent in the works of people who should have been most concerned with it, the fact does require some attention. Simply, there are no extant classical or medieval astrological texts which attribute any astrological or historical significance to precession. (Campion 2016, my emphasis).”

Accordingly, my hypothesis here would appear to be no better than any damn fool’s, unless there is a way to redeem it with solid historical or scientific evidence. I think the hypothesis is redeemable for two reasons. One is testability; the other is counter examples of Campion’s opinion.

Testability – One of the standard approaches to the scientific testing of hypotheses is to predict consequences that should be observable only if the hypothesis is correct. On this score, if my hypothesis is correct then further study of the sources for the curriculum of the Quadrivium at the Cathedral School of Chartres at the time of Thierry should find that knowledge of Al-Battani’s book De motu stellarum was a source preferred over Ptolemy in the matter of precession. On the contrary, if it is found that some other source was preferred, say Ptolemy or Origen, then that would falsify the hypothesis and justify it being rejected. The kind of evidence to look for would be a statement or comment of the kind made by Copernicus, cited below. Until this test can be performed, I turn my attention to counter examples to the opinion that “there are no extant classical or medieval texts which attribute any astrological or historical significance to precession.”

Calendar Reform and Precession – By 1582 when the Gregorian calendar was introduced by Pope Gregory XIII in the papal bull Inter gravissimas (Latin for: Among the Most Serious), the earlier Julian calendar had fallen 10 days out of step with the true dates of the equinoxes, due to precession. The discrepancy arose because precession makes the tropical year shorter than the sidereal year, we now know, by 20 minutes and 24.5 seconds. The tropical year, on average 365 days, 5 hours, 48 minutes, 45 seconds, is the amount of time it takes to observe the Sun return to the same equinox position and this tracks the seasons. The sidereal year in mean solar time of 365 days, 6 hours, 9 minutes and 9.5 seconds, is the time it takes the earth to orbit the Sun exactly once, measured relative to the distant stars. In 2009 Ari Ben-Menahem, wrote in his Historical Encyclopedia of Natural and Mathematical Sciences that the growing calendar discrepancy, caused by precession, had been well-known since the early medieval period, specifically by Bede noting a three day error in the 8th century and Roger Bacon, c. 1200, a seven or eight day error. Moreover, Johannes Sacrobosco wrote in his book De Anni Ratione (Latin for: On Reckoning the Years), c. 1235, that the Julian calendar was out of step with the equinoxes by ten days and that some correction was needed. Even Dante Alighieri, writing c. 1300, was aware of the issue and the need for calendar reform. I’m not entirely sure how historians would make sense of historical periods without a reliably calibrated calendar of one kind or another. Considering the size of calendar discrepancies that can accumulate over centuries due to precession, I would say the issue, considered by the likes of Bede, Bacon, Sacrobosco and Alighieri, was indeed of rather substantial historical significance. Moreover, the issue of precession, when calendar reform finally came, was rather aptly named as “among the most serious”.

Copernicus and Precession – The Polish priest and astronomer Nicolaus Copernicus lived on the cusp between the Middle Ages and Modern times, often pegged at the year 1500. He was born in 1473 and died in 1543. In about 1530 he completed his book De Revolutionibus Orbium Coelestium (Latin for: On the Revolutions of the Heavenly Spheres) that would not be published until 1543. This work shows not only his knowledge of Al-Battani but expresses a preference for Al-Battani’s rate of precession over Ptolemy’s: “Venus, although bigger than Mercury, can occult barely a hundredth of the sun. So says Al-Battani of Raqqa, who thinks that the sun’s diameter is ten times larger [than Venus’], and therefore so minute a speck is not easily descried in the most brilliant light […] I said, however, that the annual revolutions of the center and of inclination are nearly equal. For if they were exactly equal, the equinoctial and solstitial points as well as the entire obliquity of the ecliptic would have to show no shift at all with reference to the sphere of the fixed stars. But since there is a slight variation, it was discovered only as it grew larger with the passage of time. From Ptolemy to us the precession of the equinoxes amounts to almost 21°. (Copernicus, De Revolutionibus Orbium Coelestium Book I, my emphasis).”

This passage is clear evidence of the use of precession – the displacement of the equinoxes by 21° – in relation to measuring a defined historical period, “from Ptolemy to us.” Al-Battani’s precession rate of 54.5 arc seconds per year for the 1,362 years between Copernicus’ book and the death of Ptolemy in 168 CE gives 20.62 degrees. Ptolemy’s much slower rate would give only 13.75 degrees. The preference of Copernicus is clear. Moreover, the above passage on precession comes at the beginning of the book where precession is introduced as part of the core evidence that helps prove the Earth revolves around the Sun. In fact Book III or fully one sixth of the entire work is devoted exclusively to a discussion of precession. Considering this is the book most often credited as terminating the medieval period by triggering the greatest scientific revolution in history, it is difficult to imagine a discussion of precession in a context of greater historical significance.

The Data in the Disarray – Considering the presence in the Royal Portal of at least two Zodiac Cycles and of six or seven astrolabes, I think there is enough data or information in the sculptures to trigger in the mind of an astronomically informed observer, the idea of instrument-aided observational astronomy as a legitimate and beneficial pursuit and as a matter of natural philosophy. This connects meaningfully with the sanctification of the Seven Liberal Arts depicted over the rightmost door. Moreover, I find it most meaningful that the data in the Zodiac sculptures are astronomically inaccurate and presented in messy chronological disarray: it connects perfectly with the theological idea of disruption in the Heavens. Disarray of the heavens in the context of the end of times and of the Second Coming is fully consistent with Biblical teaching. These teachings and centuries of commentary on the theology and eschatology of Adventus warn that disruption and disarray in the heavens will be signs of the Second Coming. A few New Testament quotes illustrate the point:

But in those days, following that distress, the sun will be darkened, and the moon will not give its light; the stars will fall from the sky, and the heavenly bodies will be shaken. At that time people will see the Son of Man coming in clouds with great power and glory. Mark 13: 24-26

Immediately after the distress of those days the sun will be darkened, and the moon will not give its light; the stars will fall from the sky, and the heavenly bodies will be shaken. Then will appear the sign of the Son of Man in heaven. And then all the peoples of the earth will mourn when they see the Son of Man coming on the clouds of heaven, with power and great glory. Matthew 24:29-30

There will be signs in the sun, moon and stars. On the earth, nations will be in anguish and perplexity at the roaring and tossing of the sea. Luke 21:25

I will show wonders in the heavens above and signs on the earth below, blood and fire and billows of smoke. The sun will be turned to darkness and the moon to blood before the coming of the great and glorious day of the Lord. Acts 2:19-20

In addition, because the zodiacal information in the sculptures is in such disarray it also connects well with Scriptural emphasis on the idea that the timing of the Second Coming can be neither known nor predicted:

But concerning that day and hour no one knows, not even the angels of heaven, nor the Son, but the Father only. Matt 24:36

Therefore you also must be ready, for the Son of Man is coming at an hour you do not expect. Matt 24:36

Be on guard, keep awake. For you do not know when the time will come. Mark 13:33

Now, brothers and sisters, about times and dates we do not need to write to you, for you know very well that the day of the Lord will come like a thief in the night. 1 Thessalonians 5

But the day of the Lord will come like a thief, and then the heavens will pass away with a roar, and the heavenly bodies will be burned up and dissolved, and the earth and the works that are done on it will be exposed. 2 Peter 3:10

In the language of modern media communications, the sculptures are ‘on message.’ They are consistent with and reinforce traditional Christian teaching associated with the end of time.

The Gemini Taurus Transposition – And lastly, why do I think Gemini and Taurus were deliberately transposed in the Zodiac Window? It is really quite simple. Once you replace Ptolemy’s rate of precession with Al-Battani’s, it makes sense for a Chartrian to sideline Taurus and emphasize Gemini because now he knows it as the age in which God created the universe.

Consider the May/Gemini pane in the Zodiac Window, shown in Figure 12 below. The monthly labor for May is supposed to be hunting. However, the knight has interrupted his hunt. He has dismounted and placed his lance at rest. Instead of stalking game, he gazes wide eyed and in rapt attention at a pole standing against a blue sky, planted vertically upon the horizon line. His horse has found something worth munching at the precise point where the pole intersects the horizon. The Gemini Twins both gesture with their hands in a downward direction toward their feet. Is it just my imagination or could the body language of the knight, the horse and the twins be a glazier’s way of directing an observer’s attention to something important lower, or rather, earlier in Gemini? Could the intersecting pole and horizon line in this image somehow represent an important intersection, say of the equator with the ecliptic, at the feet of Gemini? Considering the pole and horizon intersect at 90°, while the equator and ecliptic do so at 23.5°, would there be any value in tracing lines to connect various points in this image, just to see if any interesting 23.5° angles pop-out? Well, maybe. But that could just as easily be an exercise in projecting meaning rather than extracting it. Moreover, however much fun you can have with geometrical doodling to connect the dots, I really think there is a much more important historical connection to be made in all of this.

Figure 12 – May / Gemini in the Chartres Zodiac Window

The Mathesis Connection – My hypothesis of connecting the disorder and disconnectedness of the Royal Portal Zodiac to the astronomy of precession and to numerically measured time keeping is grounded on the keen interest of the Chartrians in the business of applying numbers – the teachings of the Quadrivium – to theology and to natural philosophy. We know how keen they were to do this from their written work. The concept of ‘numerizing’ or mathematicising knowledge is known today by the word mathesis, derived from the Greek μάθησεως. It is used primarily in discussions of the historical quest for a scientia mathematica universalis or a universal science grounded in mathematics. The historical outline of this quest usually starts with Pythagoras and Plato and their late classical followers. Generally ignoring the Middle Ages completely, it then jumps straight to the Italian renaissance with the work of Marsilio Ficino and Galileo, in a rush to get to Descartes, Leibniz and then to perhaps the greatest work of mathesis of all time, Newton’s Principia, the full title of which is Philosophiæ Naturalis Principia Mathematica, Latin for Mathematical Principles of Natural Philosophy. Make no mistake: it is to the multi-generational journey of mathesis that we owe the debt of transforming what the Chartrians knew as Natural Philosophy into what we know today as Astronomy, Cosmology and Physics. And whoever overlooks the role of the Chartrians on that long and arduous journey through time, fails in connecting the dots.

Richard J Legault

26 May AD 2017 (Gregorian), Ottawa

Figure 13 – The Disconnected Zodiac of the Chartres Royal Portal c. 1145, in random order.

Richard J Legault is a freelance journalist who lives with his wife Lynn in Ottawa, Canada. Some of his astronomical work has appeared in the Journal of the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada. Some of his unpublished work-in-progress on Chartres is posted on the Academia.edu web-site. Legault welcomes questions, comments and feedback at richardjlegault@gmail.com.

References:

Ball, Philip 2008 Universe of Stone–A Biography of Chartres Cathedral Harper Collins New York.

Ben-Menahem, Ari 2009 Historical Encyclopedia of Natural and Mathematical Sciences Springer, New York. Consulted 31 May 2017 at URL:

https://books.google.ca/books?redir_esc=y&id=9tUrarQYhKMC&q=precession#v=snippet&q=calendar&f=false

Bishop, Roy L. and Turner, David G 2016 “Astronomical Precession” in Observer’s Handbook 2017, James S. Edgar, Editor, Royal Astronomical Society of Canada, Toronto 2016.

Burnett, Charles S. F. 1978 “Arabic into Latin in Twelfth-Century Spain: the Works of Hermann of Carinthia”, in Mittellateinisches Jahrbuch, 13, 1978, pp. 100–34. Consulted 26 April 2017 at URL: http://www.mgh-bibliothek.de/dokumente/a/a053253.pdf

Campion, Nicholas 2016 Astrology and Popular Religion in the Modern West: Prophecy, Cosmology and the New Age Routledge, New York.

Copernicus Nicolaus 1530 De Revolutionibus Orbium Coelestium, manuscript digital copy consulted 25 May 2017 at URL: http://pka.bj.uj.edu.pl/bjmanus/revol/plist_e.html

Copernicus Nicolaus 1543 De Revolutionibus Orbium Coelestium, (On the Revolutions of the Heavenly Spheres) translator Charles Glen Wallis, in Hawking 2002

Edgar, James 2016 Observer’s Handbook 2017, The Royal Astronomical Society of Canada, Toronto, Ontario.

Ellard, Peter 2007 The Sacred Cosmos–Theological, Philosophical and Scientific Conversations in the Twelfth Century School of Chartres, University of Scranton Press, Chicago Illinois.

Fassler, Margot E. 2010 The Virgin of Chartres – Making History through Liturgy and the Arts Yale University Press, New Haven.

Hawking, Stephen 2002 On the Shoulders of Giants – The Great Works of Physics and Astronomy Running Press Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

Hermann of Carinthia 1143 Preface of The Planisphere of Claudius Ptolemy in Burnet 1978.

Huxley, T. Henry 1873 Critiques and Addresses MacMillan and Co., London

James, John 2009: In Search of the Unknown in Medieval Architecture Pindar Press, New York.

Katzenellenbogen, Adolf 1964 The Sculptural Programs of Chartres Cathedral W. W. Norton & Co, New York.

Knitter, Brian John 2000 “Thierry of Chartres and the West Façade Sculpture of Chartres Cathedral” San Jose State University Master’s Theses, Paper 2052.

Legault, Richard J 2015a Chartres – Adventus, draft monograph posted at URL: https://www.academia.edu/11801856/Chartres_-_Adventus

Legault, Richard J and Powell, Martin J. 2015b Chartres – The Guardians of Time draft paper posted at URL: https://www.academia.edu/19747483/Chartres_The_Guardians_of_Time

Legault, Richard J 2017a A Close Encounter of the Medieval Kind draft monograph posted at URL: https://www.academia.edu/30679872/A_Close_Encounter_of_the_Medieval_Kind

Legault, Richard J 2017b Chartres Royal Portal – Ascension or Creation? draft monograph posted at URL: https://www.academia.edu/32400373/Chartres_Royal_Portal_Ascension_or_Creation

Lewis, George 1911 The Philocalia of Origen – A Compilation of Selected Passages from Origen’s Works made by Gregory of Nazianzus and Basil of Caesarea Charles Scribner’s and Sons, New York. Digital copy consulted 25 May 2017 at URL: http://www.tertullian.org/fathers/origen_philocalia_01_intro.htm

Livio, Mario 2013 Brilliant Blunders From Darwin to Einstein Simon and Schuster New York.

Mâle, Emile 1958 The Gothic Image: Religious Art in France of the 13th Century, translated by Dora Nussey, Harper & Row, New York.

Mâle, Emile 1983 Chartres Harper and Row, New York.

Minio-Paluello “Plato of Tivoli” Complete Dictionary of Scientific Biography 2008. Encyclopedia.com, retrieved 29 Oct. 2013 http://www.encyclopedia.com.

National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) Aerospace Dictionary, web site consulted 10 May 2017 at URL: http://www.hq.nasa.gov/office/hqlibrary/aerospacedictionary/aerodictall/g.html

O’Connor, John J.; Robertson, Edmund F., 1999 “Muhammad ibn Jābir al-Harrānī al-Battānī”, in MacTutor History of Mathematics archive, University of St Andrews, retrieved 29 October 2013 from: http://www-history.mcs.st-andrews.ac.uk/Biographies/Al-Battani.html

Origen c. 250 Philocalia in Lewis 1911.

Plato, Timaeus, cited in Ellard 2007.

Thierry de Chartres et al. La Cathédrale Notre-Dame de Chartres (Our Lady of Chartres Cathedral), lithoscript monument, Cathedral School of Chartres, Chartres, in phases from circa 1145 to circa 1219.

Van Der Meulen, Jan and Nancy Waterman 1981 The West Portals of Chartres Cathedral: The Iconology of the Creation University Press of America.